Homeowner and Architect

(Building a Relationship)

Architects can make dreams come true,

and our author, an architect himself, tells you how it’s done –

from initial planning through moving in

The turning point may have come a few years ago, when the country’s hottest avant-garde architect, Michael Graves, won an American Institute of Architects Honor Award for remodeling an ordinary white clapboard house in suburban New Jersey. The profession’s recognition went to the kind of job an earlier generation would have accepted only to keep their apprentices busy. There was no attempt to hide what this was: the remodeling of a typical suburban house, hitting the big time.

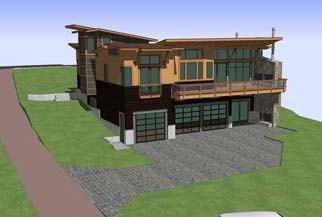

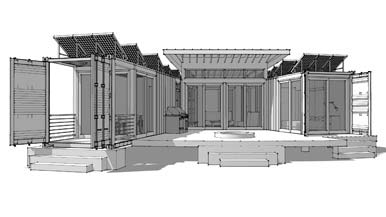

In fact, many of today’s most exciting residential designs are not rich men’s retreats. Instead, they’re space-efficient single-family houses, well-planned additions, and remodelings designed by architects working with modest budgets.

Why this change? By some estimates, we already have over 80% of the buildings we will need in the year 2000; at the same time, the number of architecture school graduates is growing. What’s more, skyrocketing housing costs and changing family and work patterns are causing once-mobile Americans to focus their time and resources on making their existing house one great place to live. The results – heightened design awareness, interest in energy efficiency, and a desire to make the most of space – have brought the homeowner’s needs closer to the architect’s skills.

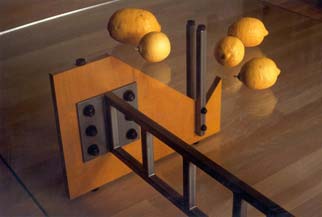

The gourmet cooking boom that is so much a part of this good life at home offers some parallels to the architect’s expanding role. Both trends share a not-so-obvious premise: that a day-to-day necessity (food, shelter) can also be a technical and artistic enterprise of a very high order. In both cases, amateurs and mass producers often do a decent job. The results are often dramatically better, however, when someone with years of training and experience is there to direct.

Architects are the master chefs of the building business. All have from five to eight or more years of professional schooling and at least three years of office apprenticeship, followed by a tough state licensing exam (see Licenses: What Do They Mean?, page 5). Unlike architectural designers, who are not licensed, or contractors, who in most states are, architects are charged to bring the same professional objectivity to their work as do lawyers and physicians. This is not to say that a contractor can’t help a homeowner add, say, a perfectly good bathroom. But would that contractor know about a terrific new whirlpool that particularly suits the room’s design? Or would he suggest that by stealing a few feet from an adjoining room he could build the new bath without expanding the exterior?

Probably not, for architects alone are actually trained as generalists to combine practical, technical and artistic skills, and to understand the building process.

Finding the architect for your house can be daunting, a bit like shopping for a psychoanalyst. This person must plumb your deepest aspirations and dullest habits. He or she may also be your comrade-in-arms in the war of attrition that is construction: a collaborator, not just a technician. This is especially true in remodeling, where your superior knowledge of your own house should mesh with your architect’s fresh ideas.

How do you find the right architect for you and your project? A list of candidates may come from friends, magazines, the local American Institute of Architects chapter, or a nearby university’s department of architecture. Then it’s up to you. You should allow several days for initial phone conversations, followed by interviews at two or more offices. And, of course, visits to at least a few completed projects are essential.

There is no real advantage to being cagey about your budget, and none to being shy. Let the firm “principal” with whom you talk know exactly what you need and want, and be honest about how much you can spend. If you’re on a tight budget, stress this from the start; conversely, you gain nothing from understatement.

Some firms you’ll contact will be one- to three-person offices, not unusual for the profession and adequate for most house commissions. Large or well-known firms may decline to be interviewed but will refer you to a talented alumnus, alumna, or to another firm. Since even the best-known architects often still love to design houses, it never hurts to ask. But prepare to interview a younger associate.

Ask questions about style and approach. A strict modernist, no matter how highly recommended, is not the right choice if you’re made about Victoriana. Architect/educator Charles Moore distinguishes between “vulnerable” and “invulnerable” architects: those who let the surrounding “context” and the client lead to a somewhat different result every time, versus those who bring a “signature” style to every job. An invulnerable architect can deliver an exquisite house with that look you’ve always wanted, but you may feel manipulated. A vulnerable one may be better attuned to your budget, thrift-shop furniture, or uptight neighbors.

Don’t be afraid to get specific. Pull out your magazine clippings – are all those cabinets, floor tiles and skylights really within your budget? An accurate answer will be neither fast nor free. In an interview, an architect should be able to size things up, however, telling you if you’re on the right track and perhaps suggesting less-expensive alternatives. Architects are notoriously optimistic about costs (which in the building business do fluctuate crazily) but reliably ingenious about getting the desired result for less money.

A more general question concerns what the architect will actually do during the design and construction process. You can usually contract for anything from advice for a remodeling to a full list of services from concept to completion, even including the design of furnishings. Time and cost will vary accordingly.

The traditional menu starts with programming. While researching local restrictions, codes and the possible or actual building site (or your existing house), the architect probes the way you live now and how you would like to live. The “program” states your project’s design “problem”.

Schematic designs, often beginning as rough, thumbnail sketches, gives you the architect’s final solution. In reality, you should toss several alternates and sub-choices back and forth at this stage, while the cost of creativity is still just time.

Does all this require a three-dimensional study model? Some architects make them routinely, others will charge a day or two of an assistant’s time to build one. These models can help – especially in seeing exterior shapes and sun exposures. But an accurate perspective drawing may tell you as much or more.

After the intermediate phase, called design development, of choosing materials, refining details and estimating costs, things become as final as they can get on paper. The construction documents, both the plans (still sometimes called blueprints, although newer processes have made some black on white for years) and the all-text specifications for roofing materials, windows, plumbing fixtures, and the like, are legally binding descriptions. They give a contractor everything needed to make an accurate competitive bid, while still allowing some leeway for time- and cost-saving alternate ways of doing things.

At the appropriate stages in the design process, your architect will help you obtain any zoning or review board approvals. The project is now ready to go to construction.

At this point, your questions will turn to whether you should retain the architect to advise on and monitor (but not “supervise” – the contract does that) construction, and on what basis the architect will get paid (see the accompanying sections).

Realize that neither the cost of the building project itself nor the fee for the architect’s service is likely to be unyielding. Don’t be embarrassed to raise the possibility of leaving some spaces unfinished, for instance. Likewise, if you intend to act as your own general contractor or do much of the work yourself, ask if design development drawings plus a few ad hoc consultations with the architect as needed won’t best serve your purpose.

Maybe the best option for you is to have all the plans drawn up now and complete the actual work in stages, as your checkbook allows. What about planning for long-term maintenance and energy savings – savings in “life cycle” costs – versus cutting the initial costs of design and construction? Does it pay to consolidate costs and fees in one big project, thereby avoiding tomorrow’s prices and interest rates? And will leaving that old radiator in place save a few dollars, but irritate you every day for the next 20 years?

In other words, take a large view, and encourage an architect to do the same. Expect him or her to think out and present your larger alternatives – and not just the financial ones. Consider hiring an architect if only because this is what architects know how to do.

– ROBERT L. MILLER.

AIAConstruction: Architect and Contractor

Once design is complete, the building process seems simple: a contractor builds, you pay. How can an architect help? First, with the architect’s help in “pre-qualifying” contractors, and making sure bid packages are clear and fair, competitive bidding can yield a good price and excellent results. Your architect can also help negotiate with a top-notch contractor: typically a fixed price, or actual cost plus a fee.

As construction starts, the architect’s role is complex but well understood. The contractor obtains building permits and begins to supervise actual construction. Meanwhile, the architect, for a fee, acts as “the owner’s eyes and ears.” He or she makes periodic site visits, reviews and approves building components, and generally confirms for both you and the contractor that things are being built as planned.

On your behalf, the architect approves the contractor’s monthly requests for payment on the basis of work actually completed. The architect also helps review inevitable “extras” proposed by the contractor to cover charges. These may include your last-minute add-ons, or come from minor mistakes by the architect or contractor. Here, the architect may be able to find a way to save the needed amount, originating a change order for a “credit”. Near the end, the architect helps check the “punch list” of unfinished odds and ends before signing the last authorization for final payment.

While basically your agent, the architect has a professional duty to further the job itself. Architects occasionally order bad work ripped out and replaced. In a dispute between you and the contractor, the architect acts as an impartial arbiter.

No architect can guarantee that the contractor whose work he or she liked on a previous job will prove to be equally reliable on yours, or that tomorrow’s lumber prices will match the projections in today’s estimate. Gross blunders in the construction documents can of course be grounds for suit. Whether or not the architect is insured for such an eventuality, litigation may offer a slim, distant payback. But on the positive side, most architects are responsible pros who will acknowledge their share in the problem, help you replace the contractor, redesign to get the budget back on track, and charge you no more.

Before the Interview: Doing Your Homework

Articles – including this one – advise you to tell an architect what you want and plan to spend. But how do you know? In a word – homework.

Know how many square feet of floor area are in your present home, especially each main room. What does the same square footage feel like in a friend’s house? In a developer’s model apartment? Then talk with a real estate agent or mortgage banker. What would your present place, and those others, cost to build or buy right now? While you’re at it, collect similar guesses for the project you have in mind, but remember that inflation and cost overruns could increase the price by 30% before you move in.

Deciding what you want and need should be part creative daydreaming, part hard analysis. Scan magazines like HOME, Progressive Architecture, or Architectural Record’s yearly house issue. But be prepared to look your present lifestyle in the eye.

Do you like the sense of space an open plan creates, or would you rather your teenage children be able to conduct their social lives in a living area separate from yours? Do you really prefer taking quick showers, or would you relax in a deep whirlpool bath if you had one? Are your guests the sort who like driving up to a formal porte cochere? Or do they usually come in the back door and hang around the kitchen? And as much as you like to look at them, could you really live in a spare, all-white pavilion? Architects often use questionnaires to help draw out these kinds of choices. One of the best such checklists can be found in The Place of Houses by Charles Moore, Gerald Allen, and Donlyn Lyndon (Holt, Rinehart and Winston). Another suggestion: Designing Your Client’s House by Alfredo DeVido (Whitney Library of Design) is new, not too technical, and enables you to look at the process from your architect’s point of view.

Fees: Pick a Basis

Traditionally, architects’ fees have been based on a percentage of construction expense – from 8 to 15% depending on the complexity of the job. Today, this sometimes seems unfair to both architects and clients. There is neither incentive nor reward for cutting costs, and the fee may not reflect work actually performed. Especially for partial services, it often makes sense to pay the architect for time and expenses, typically on an hourly basis, or to agree on a lump sum.

Some part of the fee will usually cover services of specialists hired by the architect: a structural engineer, lighting consultant, and so forth. Whatever the fee basis and services covered, you’ll usually pay the architect monthly, with the amount due keyed to whatever stage the work has reached at that point.

The fee is one factor in deciding which architect to use (or to what extent to use one at all). Still, the dollars involved are minor compared to construction costs, and a tiny part of your house’s “life-cycle” energy, maintenance, and resale balance sheet. And while there are no guarantees, an architect often saves the homeowner enough in construction, life-cycle costs and hassles to repay the fee with interest.

Licenses: What Do They Mean?

In the United States, anyone who uses the title “architect” (or the initials “R.A.”) must be a registered architect, properly educated and examined and licensed by at least one state. The initials “AIA” or “FAIA” after an architect’s name signify a member or, more honorifically, a Fellow of the American Institute of Architects. The AIA claims over two-thirds of the country’s registered architects, and members’ firms handle over 90% of architect-designed construction. Like all professional societies, however, this one occasionally provides antipathy as well as loyalty, so there are good architects who are not “AIA”. Young architects often wait to join, since they get most benefits indirectly as firm employees. Expect to pay a premium for fame or experience, but not for AIA membership.

Whether or not the architect you choose is a member, your local AIA chapter can give you help and advice. Their referral list and awards programs may suggest firms to interview. And two free booklets – “You and Your Architect” and “Your Architect’s Compensation” – provide a summary of how architects work.

The Contract: What Goes In

Your agreement with an architect for new house or remodeling design services can be covered by a simple letter contract. Alternatively, there are contract forms published by the American Institute of Architects that dovetail with the widely used AIA owner-contractor agreement forms. Whichever you choose, make sure the architect’s services and fee basis are spelled out, add any special arrangements for expenses or additional services, and see a lawyer before signing.

As with other professionals, what you contract for is the architect’s idea or opinion, not a physical product. The plans and specifications for your house remain, legally, the architect’s property. While you can sue over errors and omissions, contracts rarely exempt you from paying for uninspired results or opinions you simply don’t agree with. All the more reason to work with an architect whose expectations match yours – and to review and understand the provisions of the contract.