Working with an architect

How fees are structured /

How to work as a team /

How to make the most of it

How much does an architect cost, and what do you get for your money? These questions may seem simple, but they have many answers – depending on the nature and circumstances of your project.

What Are You Paying For?

A good architect brings both imagination and expertise to the task at hand, and can provide for both short- and long-range objectives. He or she can offer approaches or solutions you might never think of on your own. In addition to supplying the design, your architect can also give you professional guidance through the construction phase of your project.

In the words of one architect, “We provide a service, not a product.” Thinking of architectural plans as a commodity is a common misconception. As the client, you do receive copies of drawings and plans, but the architect holds a copyright on the originals (and also bears responsibility for their accuracy).

You are paying for the time that the architect must take to analyze your requirements, define what you need and want, develop and revise the design, coordinate the permit process, and ascertain that the project is built according to the plans and specifications. You are also paying for something less quantifiable: the skill to create functional but unique living spaces that are responsive to you, the client; to the site; and to the climate in which the project is built.

From the outset, it’s important to ask about fees and have some sense of price range. It’s equally important to feel that you and your architect can establish good communication and a sense of trust and mutual respect; this part of your hiring decision is personal and subjective, something you might come to only after interviews with several architects.

These four homeowners’ comments about the client-architect relationship are revealing:

“The process of designing and building magnifies characteristics and personality traits of the individuals involved.”

“You can’t treat an architect like a bartender who just listens; you’ve got to give him or her some freedom.”

“We thought it was important to work with someone who was creative, who could do more than just give us a solid structure.”

“We needed an architect who could understand our own ideas for dealing with our sloping site and then expand upon them.”

Like a doctor or lawyer, an architect is a professional qualified by rigorous training. To receive a license, he or she has to pass a series of examinations and complete years of internship. Part of what an architect learns is how to identify when consultants or other specialists are needed and how to coordinate their input.

Getting the Most from the Relationship

“House design is a personal adventure. It requires mutual enthusiasms on the part of client and architect.”

House design is also an exceptionally detail-oriented process, with great potential for getting bogged down in the myriad decisions that must be made. It is very tempting to focus on tangible elements such as paint color, say, or appliance choices, but you shouldn’t lose sight of the original reasons for undertaking the project or of the concept you and your architect have agreed upon.

Remember that though an architect is trained to be able to translate your hopes and dreams into built form, he or she can do so only if you have taken the time to analyze what it is you really need or want.

You and the architect must work as a team to come up with a plan that directs the construction process in an orderly fashion. With planning and permit rules becoming increasingly complicated, such teamwork is more important than ever.

As one AIA official puts it, “Working closely with the architect, and being careful to communicate needs before construction, is how to avoid last-minute design changes.” Those changes can be very costly in terms of both money and time; they can require new drawings, possibly invalidate permits and agency approvals – and send you back to begin the process all over again.

How Are Fees Calculated?

There’s no single method for computing architects’ fees. Representative architect-owner agreements drafted by the American Institute of Architects (a 56,000-member association which “promotes a high level of professionalism,” though not all architects choose to belong to it) specify that payments for basic services should be made monthly, but leave the method of calculating the fee entirely up to the architect. One architect’s advice:

“Ask about fees in the first interview; it helps avoid misunderstandings later.”

Fees are usually structured in one of three basic ways: as an hourly rate for time and materials, as a stipulated sum, or as a percentage of the construction cost. Many architects use a combination of approaches, such as an hourly rate for one phase of the project and a fixed fee for another, all to add up to a spelled-out maximum percentage of the construction cost. This usually ranges from 10 to 17 percent (or more) of construction costs, depending upon the architect and the size and complexity of the project.

Some architects ask for an initial retainer or advance payment to establish the client’s commitment to the project. Such a payment might be a set sum or one percent or more of the construction budget and is usually considered part of the overall fee. Generally, architects use a fixed fee for the phase of the work that they have the most control over, such as the preparation of working drawings, and use hourly rates for phases that are less predictable, like the early schematic design phase. Reimbursable expenses, such as long-distance telephone calls, printing and photography, are often billed at 1.15 to 1.25 (or more) times the invoice cost.

According to the AIA, “The basis for the fee, the amount, and payment schedule are issues for you and your architect to work out together.” One of the best ways to do this is to ask for an outline of the stages of work to be performed and the approximate percentage of the fixed fee or hourly rate that will cover each stage. Then ask what is not included in the fee so you won’t be surprised later.

Phases of the Work, Percentages of the Fee

At the client’s request, the architect, on the basis of one or more interviews, can outline the arrangements for service in the various phases of work on the project. A typical outline includes the following basic steps. The estimated percentages correspond to the amount of time generally allocated to each phase, and to a proportional amount of the architect’s fee.

5-10% Deciding What to Build

The architect takes into account the client’s budget and compares it to a rough estimate of current per-square-foot building costs. He or she outlines the program, including reviewing, verifying, or augmenting any existing “as-built” drawings (if the project is a remodel).

10-15% Preparing Rough Sketches

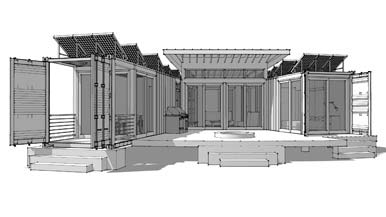

This is known as the schematic design phase. The architect develops floor plans and elevation drawings, verifies preliminary information with the appropriate planning department, and consults with a structural engineer if necessary. Often the architect provides more than one scheme, though usually no more than three.

A fixed-fee arrangement may limit the number of conceptual studies leading to one complete design. If the fee is hourly, there can be as many studies as the client wants. But, as one architect says, “If you need more than two or three complete designs, there’s something wrong.”

15-20% Refining the Design

This phase, also known as design development, is when the architect prepares more detailed drawings to fix and describe the size and character of the entire project, including systems, materials and finishes, fixtures, and equipment. The architect reviews the proposed project with local agencies having jurisdiction to allow for the orderly processing of applications, then prepares permit drawings. The architect might ask a contractor to prepare a preliminary cost estimate.

Today many architects put the neighborhood-review or council-hearing phase on a time-and-materials basis. Neighborhood and council review can also come at the end of the schematic design phase. In the words of one architect, “We have no idea how much flak we will encounter, so it’s not part of the architectural percentage.” Increasingly, application for the planning permit (as opposed to the building permit) happens at this time instead of at the next phase.

40-45% Construction Documents

The architect prepares working drawings and specifications that describe in detail the requirements of the entire project, including the necessary bidding information. Submission for the building permit usually happens after this phase.

5% Finding a Contractor

The architect does not select or hire the contractor; the homeowner does. However, the architect acts as advisor on selecting the contractor and helping the client through the bidding process.

15% Administering Construction

Acting as the client’s agent, the architect observes the construction phase with regular – usually weekly – site visits. To ensure that the project is completed as designed and specified, he or she reviews the contractor’s request for payment, reviews and recommends change orders approved by the client, and makes a final listing of items to be corrected or completed by the contractor.

There is considerable variation in what a client and architect may agree the architect is responsible for. A client, for example, might decide to be his own contractor.

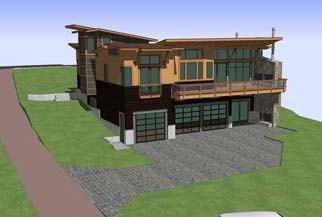

Construction time for a new house depends on individual circumstances. Among the many variables is the character of the lot: one San Francisco architect allows six to nine months for building on a typical sloped site, but nine months to a year for a very steep lot.

Remember that no two building projects are exactly alike. Two variables are the nature of the site (building in a seismic zone might require consultation with an engineer) and the cost of doing business in a particular area (in different communities, building and planning code regulations, design-review procedures, and permit requirements may demand different processing times). How much of the architect’s time the job will take also depends on the project’s size and complexity, the distance to be traveled, and the number of client meetings needed.

Inevitably, there will be unforeseen developments, some of which may delay the project and/or add to its overall cost.

Estimating Construction Costs

Even architects admit it: construction is expensive. Just how expensive depends on your own priorities. If space efficiency is important, the architect can help you achieve it. For example, your architect might be able to show you how to avoid adding costly new space by instead simply opening up a wall between two existing rooms for a more spacious feel. Conversely, if budget is not so important, your architect can show you a wider range of choices in terms of square-footage, materials, and fixtures.

“Architects design expensive homes and inexpensive ones. It depends on what the client wants.”

To get a rough idea of current local building costs, talk to several contractors and architects in your area and compare the figures they give you. When you ask them what they generally calculate the per-square-foot cost of residential construction to be, be sure to characterize the type of construction you have in mind. Are you assuming the use of good-quality materials and some (but not lavish) custom detailing? Are you assuming the inclusion of masonry fireplaces and restaurant-grade appliances? Such estimates do not usually include the cost of land, special site work, utilities, elaborate window or floor treatments, or landscaping.

Here are some specific examples from different parts of the West:

A distinctive but not luxurious 3,000-square-foot house designed by an award-winning architect for a relatively straightforward in-fill site in the western section of San Francisco cost about $325,000 to build in 1989. The fee for the architect was approximately 13% of the total construction cost, or about $42,000. (From this fee, $4,000 was for a seismic consultant and $2,000 for structural drawings.) The entire bill came to $367,000 – not including the cost of the land the house was built on.

In Pacific Palisades, California, an 1,100-square-foot, architect-designed master suite addition over a new garage – with an imaginative bridge link – cost $120,000 in 1989. The architect’s fee was an additional 10%, or $12,000.

In Portland, a just-completed 2,450 square-foot, four-bedroom, skillfully sky-lighted house on a sloping lot cost about $284,000 – plus architect’s fee of 12%, an additional $34,000.

Further Reading

General advice on what an architect does can be found in a 12-page booklet recently published by the American Institute of Architects, A Beginner’s Guide to Architectural Services. To order it, send $2 to AIA, 1735 New York Ave. N.W., Washington, D.C. 20006, or call (202) 626-7460. Local chapters of the AIA may carry this booklet, as well as standard contract documents.

Another helpful book is How to Build a House with an Architect, by Milnes Barker (Harper & Row, New York, 1988; $12.95).